BMAT Section 1 Critical Thinking Guide

Hi everyone!

In this post, we’re going to talk to you about Section 1 of the BMAT, one of the Admissions Tests you might have to do to study Medicine at certain universities.

We’ll discuss the questions, and give you lots of hints and tips that will hopefully help you ace the test!

There are two parts to Section 1 – Critical Thinking and Problem Solving. In this post, we’ll go through Critical Thinking and in the next post, we’ll talk about Problem Solving.

As always, you can flick to the parts that are important to you with the Table Of Contents below.

Table Of Contents

- What Is The BMAT?

- BMAT Section 1 Time Pressure

- BMAT Critical Thinking Question Styles

- BMAT Critical Thinking Fully Worked Solutions

- ---- [1] What Is The Main Conclusion?

- ---- [2] What Conclusion Can Be Drawn From The Passage?

- ---- [3] Identify An Assumption.

- ---- [4] Identify A Flaw In An Argument.

- ---- [5] Which Statement Strengthens/Weakens The Argument?

- ---- [6] Logic

- BMAT Section 1 Scoring

- Our Closing Tips

What Is The BMAT?

If you’ve just read that and thought ‘what the heck is a BMAT’ don’t worry!

The BMAT is an extra exam you sit if you apply to study Medicine, Biomedical Sciences or Dentistry at some universities.

Originally it was just a few places, (e.g. Oxford, Cambridge, UCL), but over the years it’s become more popular and is used by 9 Medical Schools. Here’s a full list of the universities and courses requiring the BMAT:

| Universities (which require the BMAT) | Which courses require the BMAT? |

|---|---|

| Brighton & Sussex Medical School | A100 Medicine |

| University of Cambridge | A100 Medicine |

| Imperial College London | A100 Medicine |

| Keele University | Only for overseas fees' applicants for A100 Medicine |

| Lancaster University | A100 Medicine and Surgery (and the A104 course with a Gateway year) |

| Leeds' School of Medicine | A100 Medicine (and the A101 course with a Gateway year) and A200 Dentistry |

| University of Oxford | A100 Medicine*, BC98 Biomedical Science*, A101 Graduate Medicine |

| University College London | A100 Medicine |

| University of Manchester | For some groups of international applicants for 106 MBChB Medicine and A104 MBChB Medicine with foundation year – see website for full details) |

It’s mainly used to help differentiate between lots of really good candidates, who’ll all be getting top marks at A-level/IB.

It’s made up of three Sections:

- Section 1: Aptitude and Skills (32 questions, 1 hour)

- Section 2: Scientific Knowledge and Applications (27 questions, 30 minutes)

- Section 3: Writing Task (1 essay, 30 minutes)

Each Section is sat ‘separately’, so you do Section 1, and at the end of the hour, you hand in your paper. Then you get given Section 2 to do and so on.

BMAT Section 1 Time Pressure

The thing that makes the BMAT hard is the time pressure. The questions themselves are tough but certainly do-able if you had all the time you wanted.

However, in the exam, you only get 112s per question in Section 1.

That means you’ve got to be really ruthless with how you approach the exam. If a question looks tough, skip it and come back. If you’ve spent a minute barking up the wrong tree, just make the best guess and move on.

There’s no negative marking, so you can’t be spending ages on the first few questions only to run out of time and miss a load of easy ones at the end.

This change of mindset is something loads of students find really tough because it’s very different from exams you’ve done in the past. It goes against the natural instinct to want to try and get every question right.

Those students who can appreciate this and change will be the ones who do better, so it’s important to get used to this.

1

Practise under time pressure.

2

Learn to spot the tricks the examiners use (we’ll go through these later on).

3

Look at the average scores for this section.

We’ll discuss how the BMAT is scored in more detail in the second article, but for now, note that the average score in the BMAT is half-marks – getting full marks is near enough impossible, so compare yourself not to the total score but to how all applicants do.

With that in mind let’s crack on with Critical Thinking!

BMAT Critical Thinking Question Styles

Critical Thinking is an important skill for doctors and scientists. A lot of things in science are not known for sure, so the ability to understand and evaluate arguments is critical for you to form your own viewpoints.

You’ll be given a block of text to read, making an argument for or against something. The topic could be anything, and while this can be a bit off-putting, everything you need to answer the question is in the passage, you don’t need your own knowledge. On that same note, even if you happen to be an expert on the topic, don’t bring in your own knowledge – the passage is all that matters!

Whilst the topics can be on anything, they actually only ask 6 or so questions, so it’s quite easy to prepare for.

The questions are:

- [1] What is the main conclusion of the passage?

- [2] What conclusion can be drawn from the passage?

- [3] Identify an assumption.

- [4] Identify a flaw in an argument.

- [5] Which statement strengthens/weakens the argument?

- [6] Which option parallels the reasoning used in the above argument/best illustrates the principle underlying the argument (logic).

We’ll go through each question type using an example, so you can see how to approach it.

- A place on the BMAT Crash Course

- Our Awesome BMAT Online Course

- 12 Months access BMAT Ninja

- 300-page BMAT workbook

- 5 x Section 3 Essay Edits

BMAT Critical Thinking Fully Worked Solutions

In this section, we will cover a fully worked solution for each and every type of question that you can face in the Critical Thinking section of the BMAT.

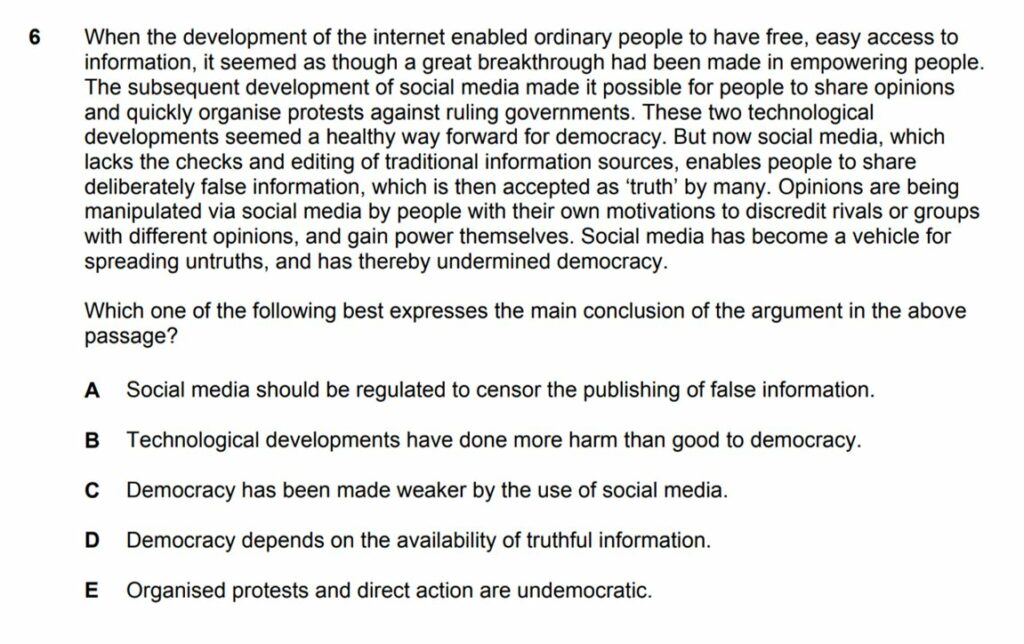

[1] What is the main conclusion?

The conclusion here is given to you at the end of the passage. ‘Social media…has undermined democracy’ is analogous to ‘democracy has been made weaker by the use of social media’.

It won’t always be as clear cut, and sometimes the conclusion will be embedded in the middle of the passage.

The most common incorrect answer students put here is B, and this shows how you really need to pick out the information in the passage and be specific.

Yes, social media is technological development, but the passage states that the internet helped democracy by empowering people, and there’s no way from the passage to tell the relative impacts.

This is a common theme that will come up time and time again. Look for the most specific conclusions, rather than grand sweeping statements. The bigger the statement, the more likely an assumption or a flaw is undermining it.

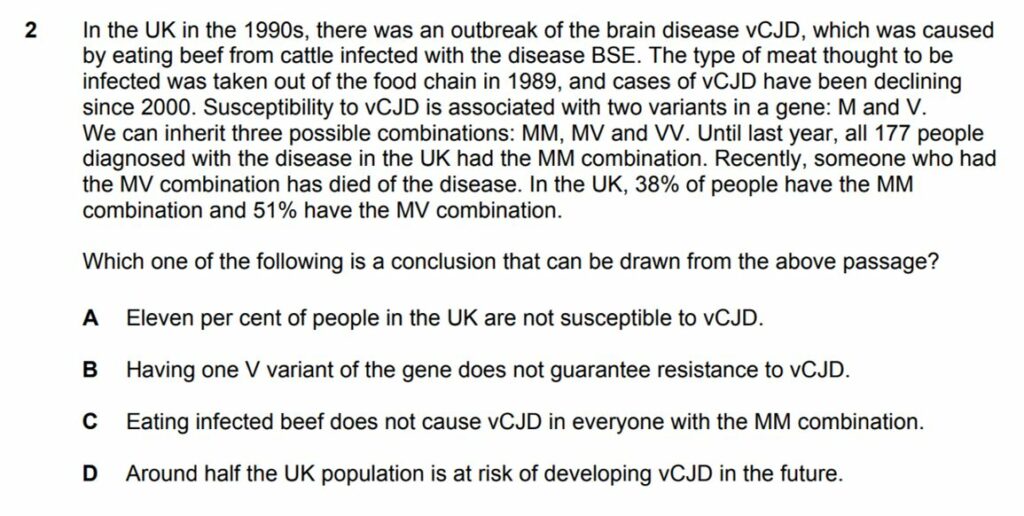

[2] What conclusion can be drawn from the passage?

Let’s look at what we’ve been told.

- cVJD is a brain disease caused by eating infected beef

- Infected cows aren’t around anymore

- The gene to do with cVJD has three combinations

- Everyone who died of cVJD had MM until last year -> so this is going to be the bad variant

- One person with MV died

- 38% of the population has MM and 51% has MV variants

Now let’s look at the options.

| A. 11% of the population are not susceptible to vCJD | This option is concluding that having the VV variant makes you immune to vCJD. This is incorrect, as it’s making a lot of assumptions not given to us in the passage. There’s no evidence to suggest that VV people are immune, it just assumes that because no one with VV has died, they must be immune. However, there are several problems here. Only 177 people have died, so you’re looking at a very small sample size, and it’s a small minority of the population who are VV as well. Also, it’s taken 18 years or so for the first MV variant patient to die. Perhaps the variant you have affects how quickly you die, and in 20 years’ time from now we might see VV deaths. |

| B. Having one variant of V does not guarantee resistance to vCJD | This is the correct answer. This is a simple conclusion, going directly and only off what information is given in the passage. One person with MV has died, so therefore V does not guarantee resistance. |

| C. Eating infected beef does not cause vCJD in everyone with MM combination | This is a more subtle incorrect answer. Given only 177 people have died of cVJD and MM is really common in the population, you could be forgiven for reaching that as a conclusion. However, there is nothing concrete in the passage to back that up – it’s assuming lots of people ate infected beef, when perhaps only those 177 people did, there’s no way to tell. |

| D. Around 50% of the population is at risk of developing vCJD in the future | This is like C. Yes, 50% of the population are MV and we now know they are susceptible, but we don’t know how many of them ate infected beef. |

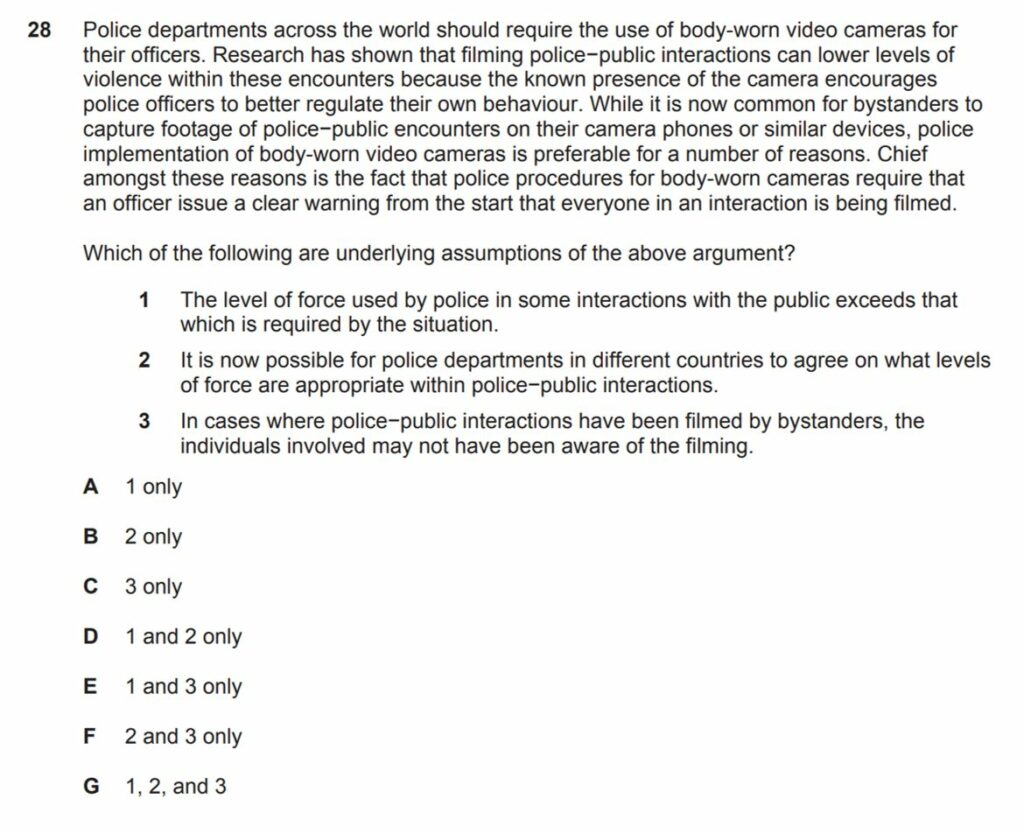

[3] Identify an assumption.

Taking it right back to basics, what is an assumption?

An assumption is something that, although unstated, needs to be true for an argument to be valid. Looking at the passage, there are two parts to the argument for police body cameras.

First is that cameras encourage better police behaviour to the public. Statement 1 would be an assumption underlying this – if you read it through, the level of force the police use must sometimes be excessive, or else they wouldn’t need to be filmed.

Likewise, with the second part which states body cameras are better because officers must warn everyone that they are being filmed, this would only be necessary if the public weren’t aware bystanders were filming them, making statement 3 a true assumption.

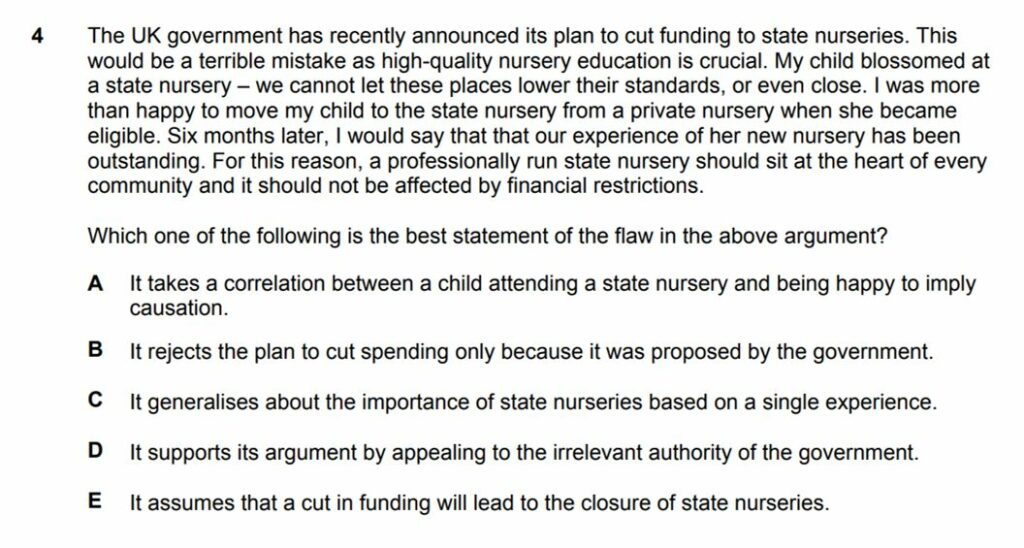

[4] Identify a flaw in an argument.

The correct answer is C.

Often these questions look a bit intimidating, but simplicity is key. This is a classic example where one experience is used to justify a viewpoint.

Often, the flaws are things we talk about in science all the time – not doing repeats to ensure reliable results and saying something is true or false all the time (which is really hard to prove).

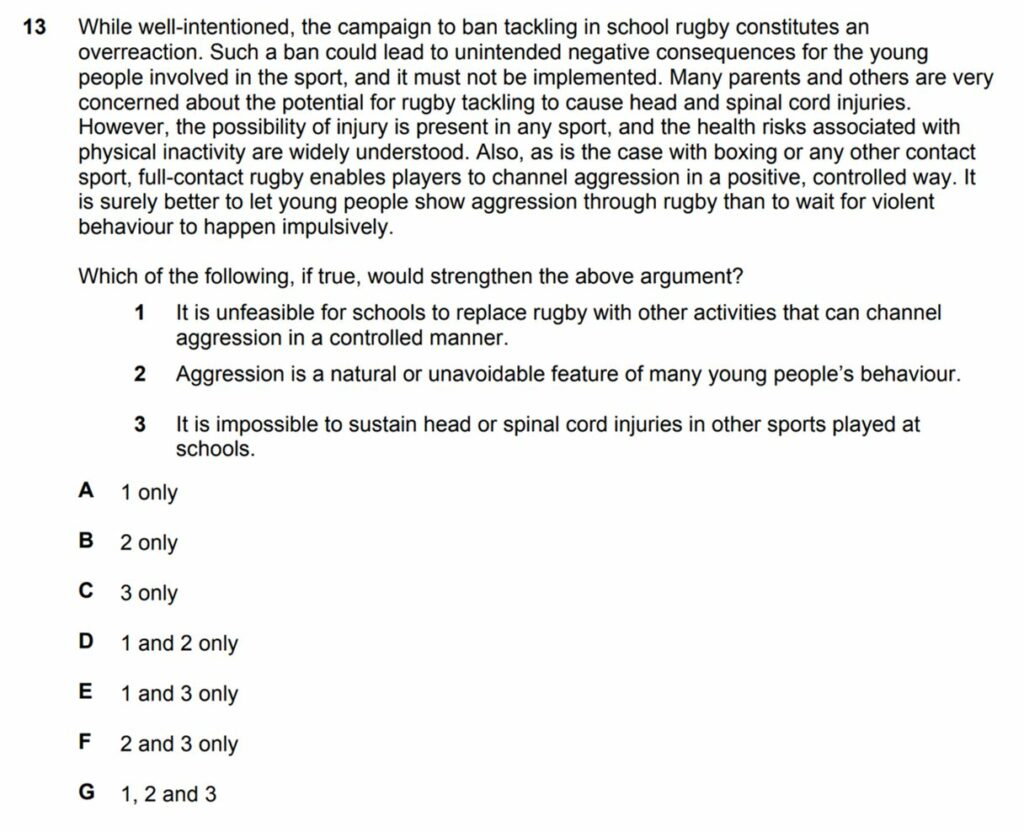

[5] Which statement strengthens/weakens the argument?

There are two parts to these questions, but hopefully, they’re reasonably straightforward.

First, you need to understand what the passage is arguing. In this case, rugby and other contact sports allow young people to channel their aggression, so that they aren’t going to be violent in the community/outside sport.

Then go through the statements and decide if they would strengthen or weaken the argument, as the question demands. Often the options will provide more information or clear up an assumption.

Statement 1 supports the argument, as it says rugby is the only form of controlled aggressive sport you could play in school.

Statement 2 also supports the argument, as it gives more weight to the point that without rugby, young people will be violent in the street.

Statement 3 weakens the argument as it says that rugby is the only school sport where head or spinal cord injuries are possible, so there must be better ways for children to be active.

The questions we’ve gone through above are the most common and most standardised. However, from time to time the examiners like to chuck in a more out-there logic puzzle.

Don’t worry if you’ve never studied philosophy or logic formally before, you can still work it out your own way, just have a think and remember if you aren’t getting anywhere after a minute or so just guess and move on.

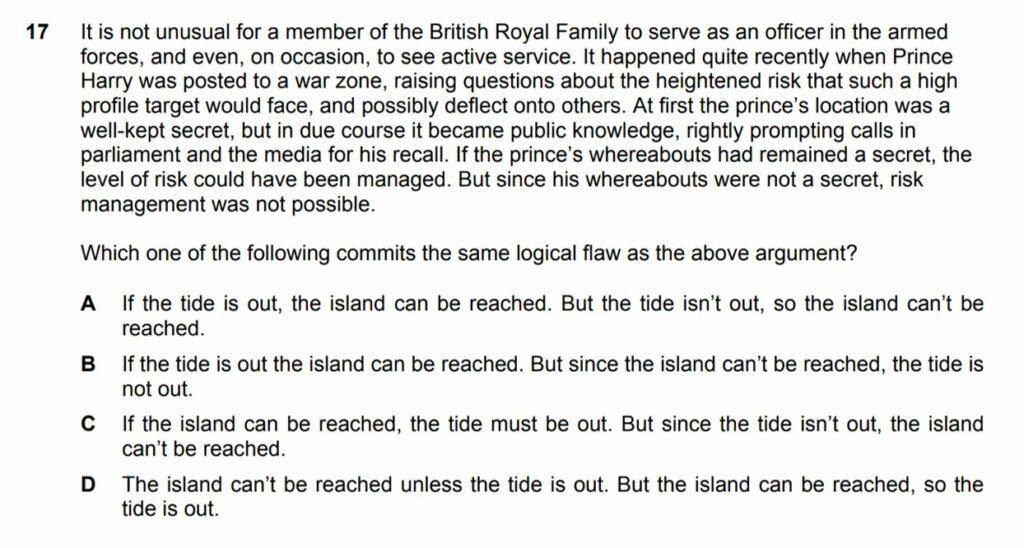

[6] Which option parallels the reasoning used in the above argument/best illustrates the principle underlying the argument (logic).

The key sentences in this passage are the last two: If the prince’s whereabouts had remained a secret, the level of risk could have been managed.

But since his whereabouts were not a secret, risk management was not possible’. There’s a couple of ways you could run with this.

One would be to try and draw parallels between the options.

Here, the tide is analogous to the prince, and the island is the risk. The tide being out is like the prince’s whereabouts being known, and if the tide is out the island can be reached (aka the prince is at risk).

So therefore, if the tide isn’t out, the prince’s whereabouts aren’t known, and the island and the prince can’t be reached.

This might not work for you, and that’s OK, find what works for you!

If you’ve got a bit of time before the exam, it’s worth having a look at some logic stuff, it’s really interesting and it’s quite handy to know some when you debate mates studying philosophy!

Otherwise, just go through the past papers and find a way that works for you, and again remember we aren’t aiming for full marks. Think tactically, if it doesn’t seem obvious just guess and move on. You lose nothing and the time you gain might help you answer the rest of the questions.

BMAT Section 1 Scoring

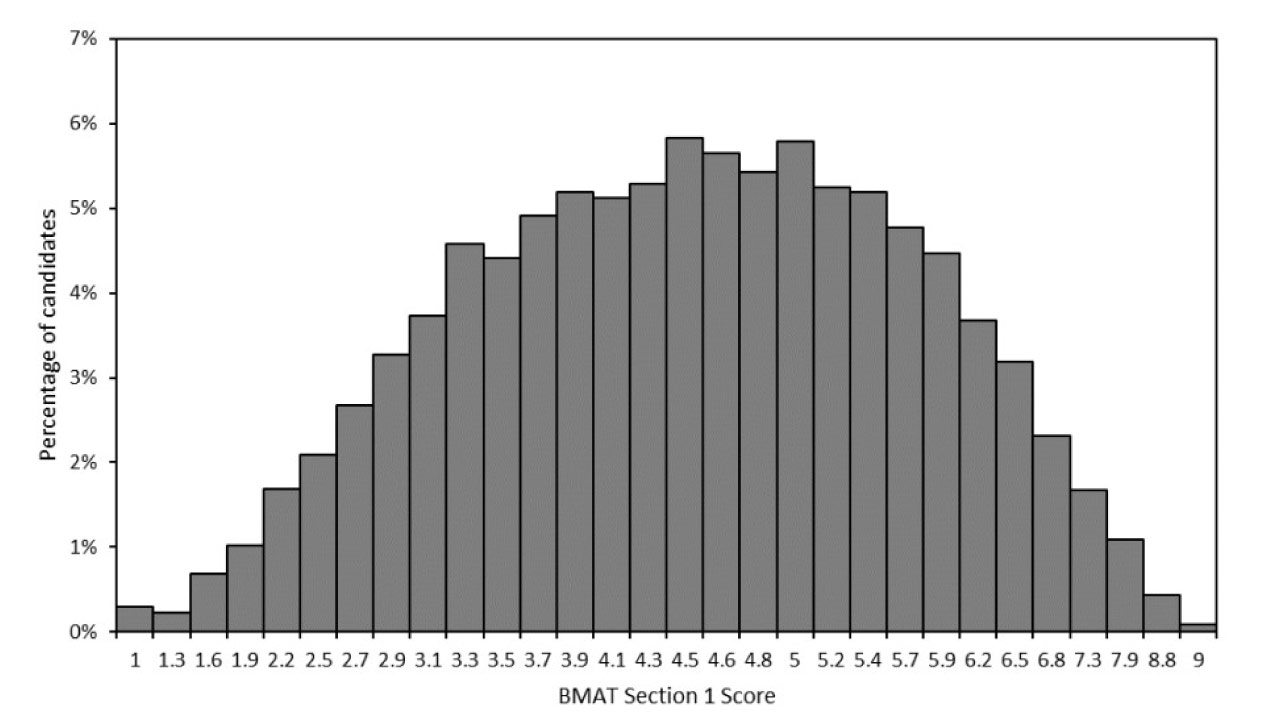

Section 1 of the BMAT is scored out of 32 total marks which are converted to a scale from 1.0 to 9.0. This isn’t a linear scale – here’s a rough chart of the conversion (please note, this changes each year:

| BMAT Score | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 9.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Marks [Section 1] | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 34 | 35 |

Have a look at the results from 2020:

In Section 1, 25% of test-takers scored between 5.0 and 6.1 and 10% of applicants scored over 6.2. Extreme scores are rare.

You don’t have to get that many more marks than the average of around 4.5-5.0 to put you up in a high decile to really stand out – and full marks are definitely not required!

Perhaps more important than scoring is understanding how universities use your BMAT score. A little research here can improve your chances quite a lot.

Some universities use the BMAT as a screening tool (you can read more about this on our BMAT scoring and results article here). Others don’t operate with a cut-off.

Medical Schools have a ton of strong applicants that they need to whittle down. The difficulty of the BMAT allows them to begin this filtration process more easily. Other universities use the BMAT holistically amongst the rest of your application.

- A place on the BMAT Crash Course

- Our Awesome BMAT Online Course

- 12 Months access BMAT Ninja

- 300-page BMAT workbook

- 5 x Section 3 Essay Edits

Our Closing Tips

If you’ve stuck with this post all the way to the end, then thank you, there’s a lot here but hopefully you’ve found it useful!

Here’s a summary of the top tips for Critical Thinking to take away with you:

1

Practise under time pressure.

It’s easy to do well in the BMAT without the pressure of the clock weighing down on you. Always do mock papers in timed conditions.

2

Do all the past papers.

Be systematic and write down why answers are right or wrong to start seeing the patterns. You should also be careful not to exhaust all the past papers too early – work on concepts first then test yourself using the past papers.

3

Simple conclusions are the best.

Big sweeping statements or generalisations are often wrong.

4

Half marks is the average score.

Don’t get discouraged if you aren’t scoring top marks like you’re used to. The more practice you do, the higher your score will get.

Next time, we’ll talk about the Problem Solving questions, and go through how the scoring system works and what it means for your Medicine application.

Hope to see you there!

If you’re looking for extra support with the BMAT, check out the awesome BMAT Bundle for EVERYTHING 6med have on offer for the BMAT.

- A place on the BMAT Crash Course

- Our Awesome BMAT Online Course

- 12 Months access BMAT Ninja (Used by 1 in 2 applicants)

- 300-page BMAT workbook

- 5 x Section 3 Essay Edits